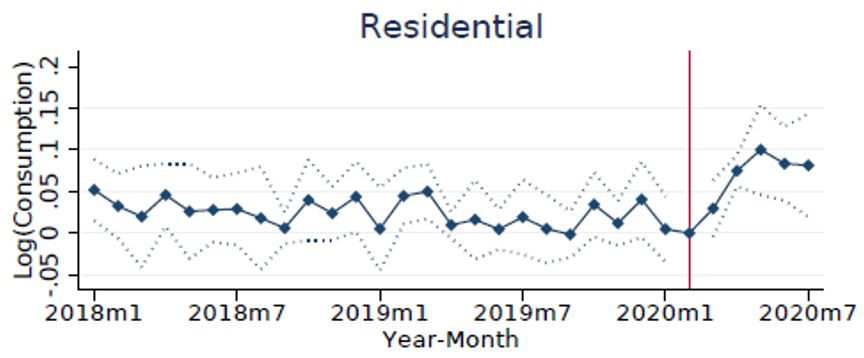

Spring shutdowns across the United States in response to the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic created substantial shifts in who was driving demand for electricity.

In short, industrial and commercial users of electricity – stores, offices, and factories – went dark while residential consumption shot up as people moved to work and school at home.

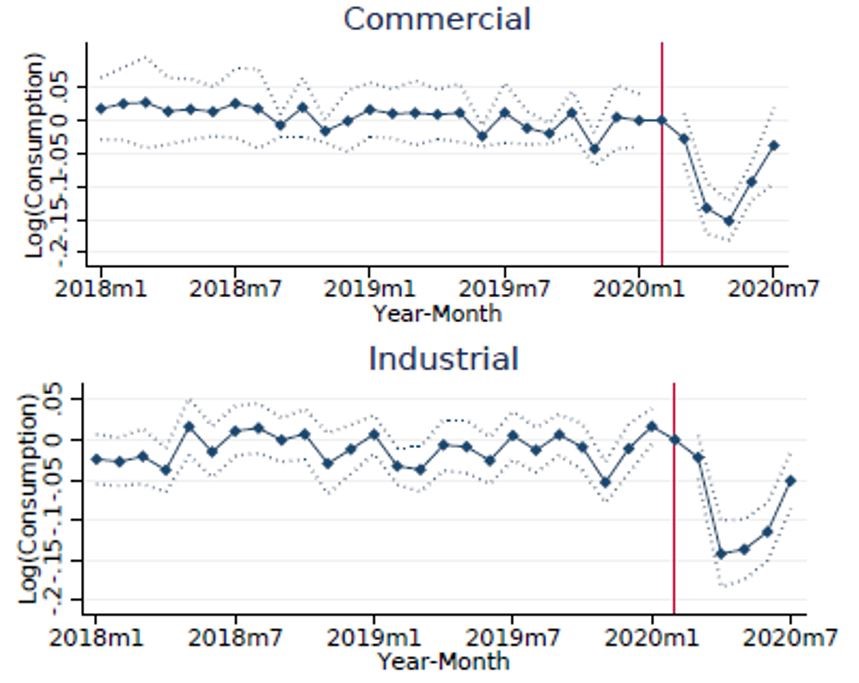

Tufts University economist Steve Cicala has studied the effect of the pandemic since it reached the United States in March. His research shows that U.S. commercial electricity consumption fell 12 percent during the second quarter of 2020. Industrial consumption fell 14 percent over the same period.

The second quarter was the worst quarter for the U.S. economy in over 145 years, with GDP falling by 32.9 percent. Schools and offices closed and manufacturing facilities shut down production. As such, there was less need for heating and cooling, less refrigeration, and a reduced need for energy-consuming computers.

But the shifts don’t stop there. All of those workers and students heading home had the opposite impact on residential electricity demand, according to Cicala’s research.

The drastic differences between residential and commercial and industrial electricity usage leveled off by June and July as more businesses reopened and some workers found safe ways to return to the office.

Does energy usage relate to the economy?

Economists have long used electricity use as an indicator of U.S. economic activity, bolstered by the fact that manufacturing accounts for a third of all energy consumed in the U.S. The correlation between growth rates in real GDP and electricity use can be as high as 89 percent, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

“Electricity is one barometer of the economic well-being of the industrial sector,” says Paul Cicio, president & CEO of Industrial Energy Consumers of America. The IECA is a nonpartisan association of manufacturing companies that promotes affordable access to energy to compete in domestic and world markets.

“All manufacturing requires electricity and natural gas to produce goods. A decrease in electricity demand signals less manufacturing output,” Cicio explains.

While the shutdowns were bad for industrial users and their output, Cicio says he has not heard of manufacturers expressing that they saved money on energy costs this year.

“We may have used less volume, but the unit costs have not decreased,” Cicio says.

How does energy demand affect electric rates?

The shift to more residential energy demand could be good for electric utilities, who earn a higher profit on residential bills than commercial electricity bills, says Albert Lin, executive director of the Pearl Street Station Finance Lab.

The Lab is an initiative providing the financial expertise to help clean energy stakeholders model, educate and implement clean energy solutions into the marketplace.

“We agree with the analysis from Steve Cicala and view the pandemic’s shift in energy use as financially favorable for most utilities,” Lin says. “Residential rates are usually higher and also have higher margins compared with commercial and industrial users.”

Lin says the pandemic shifts create less efficient energy usage, since it is more efficient to have many people working in one air-conditioned building than for each of those individuals to cool their own home during the peak heat of the day.

Hourly smart meter data from Texas used in Cicala’s research reveals how daily routines changed during the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, Texas households used the most electricity on Saturdays and Sundays rather than on weekdays. During the lockdown, every day was similar.

Not surprisingly, the biggest declines in commercial and industrial electric demand were during regular working hours.

Cicala’s research compares the Covid-19 recession to the financial crisis of 2008, which also sparked a quick drop in industrial electricity consumption. Yet then, residential usage was unchanged.

By the end of May, Cicala said overall demand had largely returned to normal with increased residential demand making up the difference for the drop from businesses that remained closed.

These changes mean the expense of powering work and school computers and providing heating and cooling shifted this year from businesses and schools to households. On average, Cicala expects the average household to spend $250 more for electricity this year. There are significant regional differences, he said, with California residents likely paying $600 more this year for electricity.

Lin says he expects the increased utility costs for households will remain as companies are happy with the efficiencies of employees working from home.

“Since the remote working behavior has been going on for so many months, many of the changes will be permanent and the companies will want to continue the productivity boost and savings,” Lin says. “The peak of savings and productivity may moderate downward if a successful vaccine and/or testing program becomes pervasive and effective, but it’s highly doubtful the world is going back to what it was prior to the pandemic.”

Laura Williams-Tracy is a freelance writer who contributes regularly to American City Business Journals on a wide range of topics and covers business and finance issues for sectors of the commercial real estate industry.

Originally Published on SaveOnEnergy.com